From selfing in worlding to sovereignty

meika worlding Iris Murdoch's Wittgenstein

I’ve been reading someone else’s copy of Iris Murdochs’ Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. (London: Chatto & Windus, 1992. ISBN 9780701139988 (article) over the last few weeks. By “someone else’s copy” I mean it has pencilled marginalia like Astute Observation. Now I have met the previous owner, so these words read themsleves aloud in his voice.

It’s been slow going, not because of the marginalia, nor Iris Murdoch’s writing, nor the subject matter, but because other books, life… and —my interest in this subject matter is intense, so every other sentence or marginal note, pulls me up thinking for a couple of hours.

In these moments I find out things, like what this blog is doing in the world is the work of moral philosophy. I type that as if I did not know that, but let us say I have been reticent to acknowledge that, this is because the straight definition of moral philosophy is of little interest to me. For on that linked three-part definition I am concerned with meta Meta-[ethics].

And how that trickles out into the world.

I hope I leak well. If I leak well… —I world well.

Anyway, with Iris Murdoch’s Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals I am up to end of the bit in the book where I read fast, because interested, but when the setting the scene is over, and the real meat of the author’s dish is beginning to be chewed, I grow distracted: art, religion etc. these are mere worlding and world-building outcomes of the selfing/worlding process as practices, rites, & strange parties.

In a book of fiction reading faster means I am getting absorbed into the world of the novel, and will not notice mistakes, unlikelineses, or even a formulaic hackness of style so much, as, as-if, the story can reduce fact-i-ness to the odd annoying speck of dust. In a book of not-fiction, even if it is unreal, my speeding-up means that I am not spending effort to integrate the writer’s efforts. For fiction speed is good, for non-fiction not so good. And I wish we had a style of forking so I didn’t have to read the same introduction to science/evolution/cosmology in every sciencey book.

(I’ve just defined the future of the book.)

However, if one is unfamiliar with a topic those normative introductions can be very illuminating. It might be one’s first introduction into a whole area of thought.

With Iris Murdoch’s Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals it is more like a refresher. But a really, really hard refresher, not necessarily in understanding but integrational multiplying effort. Not in metanoia but in taking in the vista before me… familiar but…I had to keep stopping… and writing paragraphs… after reading one sentence. What a language game that is!

Some decades ago I went with Nigel Farley to see the movie Wittgenstein at the State Cinema in North Hobart. On leaving we met up with Raymond Rohner also leaving. and had coffee at the Reknown Milk Bar, and discussed our previous encounters with Wittgenstein. A couple of years later I borrowed from my to-be brother-in-law Ray Monk’s Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. (1991 London: Vintage.) So impressed with this I bought a copy which I later gave it to Workineh Kelbasa of Addis Addiba, though I think he was visiting Hobart, for a conference on fire, from the Netherlands at the time. (I am worlding for you, whoever you are.)

And so Wittgenstein has always been a thinker I’ve been meaning to get back to more deeply, and more directly.

Since I started this blog in January (its now August 2023) the genius of duty has had a few mentions, but as yet have not got back into it. This is because the corpus of his Nachlass is available online (described in this PDF, so see also CLARIN), and I have enough German to give it a go more directly, but where is the time?

I mentioned those friends names meeting in the Reknown, because my re-introduction to Iris Murdoch is via a search for the previous owner of a book of poetry from the 1940s, and the only mention I found of her (maiden) name was on a guest list to a party at Iris Murdoch’s flat.

I had, previous to this, only read Iris Murdoch’s novels, and usually collected from op-shops. I remember getting Under the net from a Vinnies thrift store that used to be in Argyle St, Hobart, in the same purchase with some unused black leather shoes in the very early nineties. I remember exploring a world in Under the net that came back to me only when I discovered that guest list.

Previously when blogging a reading-in-progress I say to myself I’ll do another post or three as this book is worth it, and then I get to read the rest of the book, and feel… —maybe not. I’ve been thinking this is bad, and I should wait until I read the whole book, but then the fire might be gone so…

—completeness is a bug not a feature… —maybe.

So, to the meat of this post

Irish Murdoch’s use of Wittgenstein’s World (Welt)

I prompted Microsoft’s Bing’s chat about Wittgestein’s use of world and it came back with:

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s view of the world is that it consists entirely of facts. Human beings are aware of the facts by virtue of our mental representations or thoughts, which are most fruitfully understood as picturing the way things are. Wittgenstein saw language to function in a similar way through it providing people with a picture of the world, which is made up of facts. For example, the words “sky” and “blue” are the building blocks of the meaningful statement “The sky is blue.” These words act as a picture of a fact within the world 1,2.

I hope that helps! Let me know if you have any other questions.

Learn more: 1. philosophypages.com2. jamesbishopblog.com

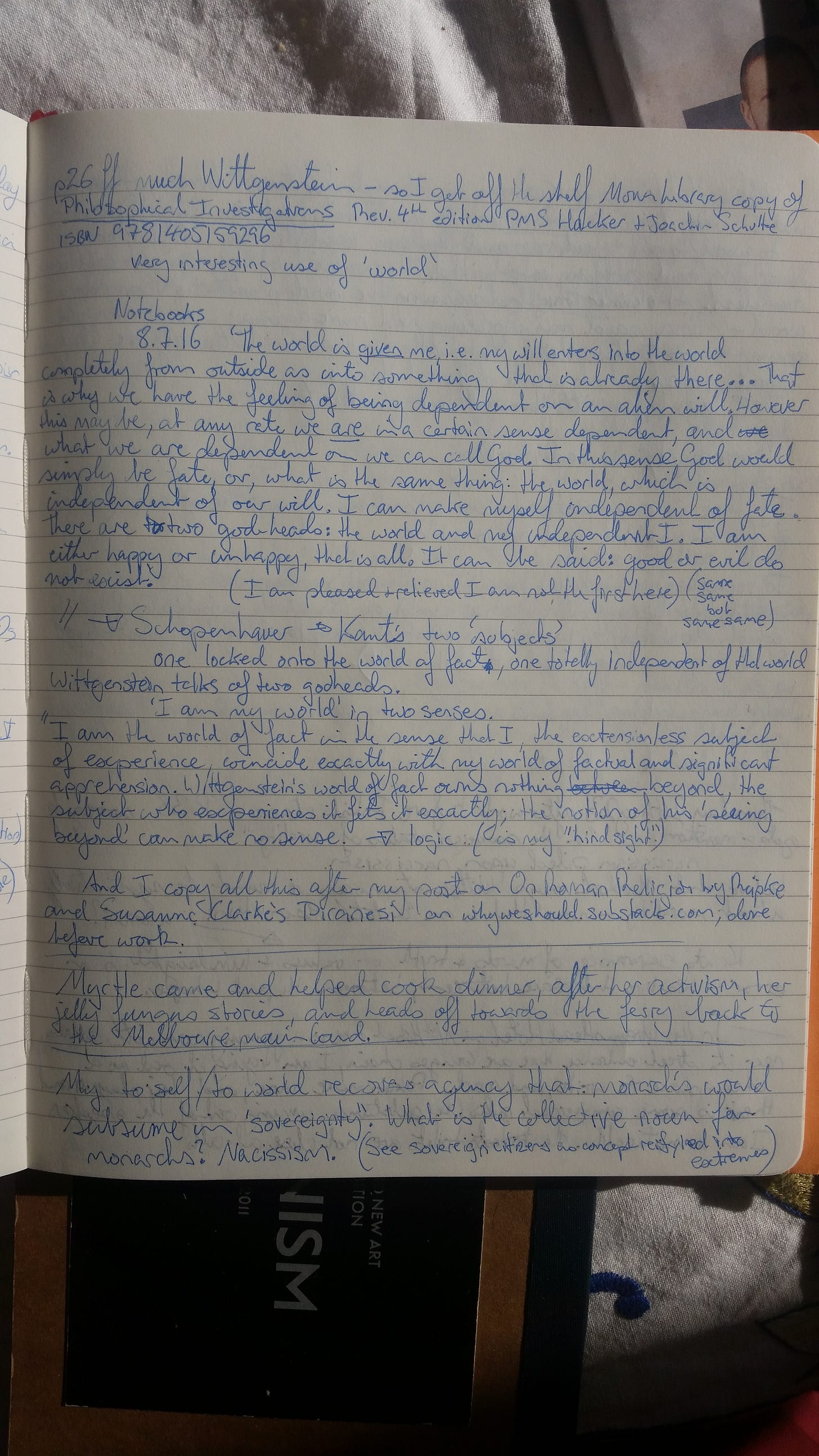

Irish Murdoch’s use of Wittgenstein is to prepare the way for her Gifford Lectures of 1982, to be turned into the 1992 book. This is to open up the processes Kant defines in ‘two subjects’, and Iris Murdoch says that it appears Wittgenstein discovers through reading Schopenhauer. (Page 26-ish) I paraphrase thus: One subject locks onto the world of facts, while one is totally independent of that world, while Wittgenstein talks of two godheads— ‘I am my world in two senses’.

“I am the world of fact in the sense that I, the extensionless subject of experience, coincide exactly with my world of factual and significant apprehension. Wittgenstein’s world of fact owns nothing beyond, the subject who experiences it fits it exactly; the notion of his ‘seeing beyond’ can make no sense.

This fits with my one-liner that logic is a hindsight.

And I read it soon after writing and posting Piranesi, the shepherd worlding their selves last week.

So.

Logic has no future? I wonder. Does that make sense? Regardless, what world would it then make?

Iris Murdoch quotes from the Notebooks 8.7.16 (and from Wittgenstein the quoting here is extensive) (there are asides that the then pre-1990s-ish infatutaion with deconstruction/ post-modernism is unaware of similar/better work done pre-WW2)(much like my complaint that modern art impresses those, who, while reading much, never read science fiction) anyway to the quote as I type it up from my handwritten notes in my red moleskin notebook:

‘The world is given me, i.e. my will enters into the world completely from outside as into something that is already there … That is why we have the feeling of being dependent on an alien will. However this may be, at any rate we are in a certain sense dependent, and what we are dependent on we can call God. In this sense God would simply be fate, or, what is the same thing: the world, which is independent of our will. I can make myself independent of fate. There are two godheads: the world and my independent I. I am either happy or unhappy, that is all. It can be said: good or evil do not exist.

At the opening ‘The world is given me,’ I had a full ten minutes thinking about what the German grammar might be here, what does this even… —thus the discovery of the Nachlass online.

And then I though same-same but same-same in my differing usage of world, but which pivots on the same notice, but not using the same leverage of words (not the same framework), not quite.

My pair “to self/to world”, my Janus metaphors, the two that is/are then mother to the ten thousand things, mediates reality. And all these separate things are only fractally separated, and bleed like anything.

I use world to refer to those practices we live, which do not refer to our selves, but still arise in the very same processes of life as the body our self: (to world/to self) a fractal complex selfsame life.

That is between that which we live as self and that which we live in the world is a fractal-like separation which we live (by selfing/ by worlding). We are this gap we cannot see clearly, even as we distinguish it as we are.

With reference to the Wittgenstein's world of facts which language models or pictures, I would pose this is what I mean when I use the term reality, which the world mediates in a similar fashion to how we live the self in worlding, or how Janus-like we live the world in selfing. Yes we do this a lot in language, but it is no god, no godhood, nor god substitute, nor idol, nor iconoclasm, even in image of our selves in our worlds.

The world mediates reality in a similar fashion (fractally) to how we live in selfing/worlding in the world. In how we mediate the world, just as we world/mediate reality. This world mediation is a social thing, even when it is not socially constructed.

Because we cannot see this clearly, we have great difficulty defining the fuzzy terms, let alone their responsibilities that we do not take up upon ourselves.

Duty is the smallest part.

To self and to world are the same responsibilities with which we mediate various realities of various hardness, or softnesses, of sweetness and light.

With regard to sovereignty

When worlding is only allowed to be done by the monarch, we call this “construction” sovereignty. This is why narcissists seek to top rather than topple the hierarchy, they are trying to make the whole thing consistent (with themselves) as they world self. Inversely, this is why being a narcissist is facultatively or functionally required for being a monarch. Power absolutely corrupts the absolutely corruptible, where such a system is taken to be a norm and not policed but warrior-ed like baboons.

This is also why a monarch has subjects, and the population under control are not citizens of a locality or industry or any other identity or calling. So calling this selfing a subjectivity is an error that favours the sovereign-monarchical state as their most preferred worlding pattern. (The city of god is a shell game.) There can only be one one.

In contrast citizens are likely worlding peeps, citizens who world and self within not for a political reality, regardless of the city as world or not.

The beauty of monarchies is that the firm in power can portray themselves as a family, a social scale most can relate to, and thus integrate into their worlds as we peeps self along as mere subjects as objects, where the soap opera of the family firm’s travails and tribulations can be enjoyed humanly as possible and so never questioned. This is the stability supporters of monarchies speak of, but I doubt the numbers are in their favour (they also all want to be the monarch one one, so… —how do we choose?).

No questions please, don’t look up.

Sovereign citizens take the worst of all such narcissistic monarchic worlds and combine them into the self itself. This atomises the worst of our collective worlding arrangements and try to live this among others, where everyone is king. An egalitarian stupidity. Like saying everyone should be rich, knowing that we are all each above average.

What is the collective noun for a bunch of monarchs? A narcissism.

Sovereignty is the wrong place to start worlding.

Iris Murdoch theme list