In traditional English habit when one worries about the meaning of words we take a descriptive rather than prescriptive attitude, that one ought not should words.

Thus large English dictionaries hoard examples of use of a word or term. It’s a point of pride for English speakers, much to the chagrin of native-born grammarians, our erstwhile traditionalists, and those of a definite bent.

Here etymologies, now often extensive genealogies of use, gain primacy as we track how people spoke their words into their worlds. And vice-versa.

Now a grammarian can gain some definition by focusing on the first recorded use, and use this to say what a word really means, but even this is frowned upon, even when the historical record, the corpus, that now scary word, is complete and well-structured.

I am not a grammarian so I use these lists of older usages for just how they portray and betray the world of those past speakers.

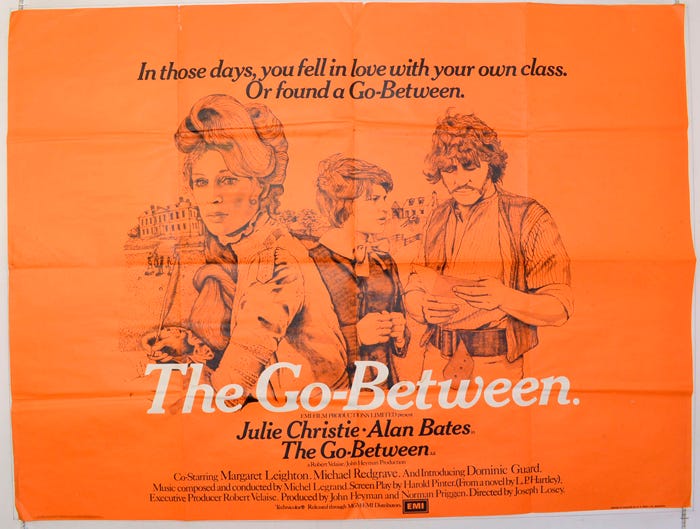

As we know from L.P. Hartley’s The Go-between, we can do this in our own lives. The old man at the very beginning of the novel, thinks back on/of himself as a boy, the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.

Of world we find it is of a Germanic combination, while it’s parts are Indo-European. It’s literal meaning is Age of Man, at a time when this included all human beings, millennia before an Act of Parliament reduced and confirmed (damned those prescriptivist grammarian radicals who think they are conservative) man to the class of adult males.

The usage that created this sense of the world combined *wer and *ald.

Human + to age/aging

This was used to refer to the middle realm, those who live/age on the earth. And not those dead below or behind us, or skied above and gone ahead of us with the godlike sun and heroic stars.

Used here is an extended sense of here and now roundabout us in the world.

I would make it thus: world pivots on hope and empathy, while holding in regard home and everything we are concerned about.

It’s poetic, a making, a survival practice, not a logic. Evolution does not care about logic, or reasons, or even emotional reasons. Not really. That’s what we do in the face of it.

So when I use this word world it is this sense of everything we worry about us, while making do.

It does include trees falling, not because we hear them fall but because we worry about that as possible event and its attendant epistemological enquiry. The world includes that which is excluded, as long as it is worried about. It may thus include unknown unknowns, at a stretch.

The world can do this, because the world is not really there, even if we consider it to be real. The world is more than its imaginging BTW (note for later).

Not that the world is unreal.

It is just that the usages of ‘real’ and the ‘world’ refer the the same thing, but in different realities or worlds.

Strangely though, the world, as I use it, includes the real, but the real may not include the world.

Possibly, what’s real about the world is that it is our extended phenotype, like a cocoon, like the earth is to an earthworm, it’s an socially spun umwelt as real to us as our self-consciousness. It’s the earth to our selves, and that’s why we can pathologically confuse the two, as narcissists do. As psychopaths want.

Yesterday is gone, but we remember it, tomorrow is not yet but we plan for it, in routine expectations and unsettling fears.

That is the world.

Like narcissists, empires seek to become the entire world, and a totalitarian regime always has the entire world consciously in its sights. Including the one in your head.

Religions, by this ‘definition’ attend to that aim, sometimes to get what religion wants, a city of god, sometimes as a mere functionaries or consultants of the empire. That’s why religions worry about belief/s, as a shibboleth of obedient indentities. Faith is a tribe.

Where there are empires there are religions. Where there is politics there are groupings. Thus the confusion the tower of Babel gets blamed for.

But we can always imagine life beyond the empire. Even as empires and the poor are always with us, the world is ever escaping an empire or two. The empires come and go, while the world is always more than this.

The world is a poetic making. (I’d say poetry but that would be currently annoying, thus the redundancy.)

Philosophy cannot help us much more than religion, where it argues in analysis of the real as a Homeric battlefield where the excellent warriors vindicate truth from the clutches of the lie. Logos as conflict where the clear-headed decapitate the fallen. This is not good.

Making peace a form of war is what empires do.

An eternal Valhalla of the dialectic is no way to build the world from-/-within reality, a Vahalla where every dawn arguments are raised from the dead to fight again about iron angels dancing on bronze pinheads. Like an argumentative LLM counting words within matrices all the way down into the past un-futured by the present.

For the world tomorrow is our last hope.

Who will think of the children?

This week’s reading:

Finished: Alasdair MacIntyre’s Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (Notre Dame, Indiana. University of Notre Dame Press, 1988) ISBN 9780244509934 (Good book but overtstates the case that language/worlds have untranslateable impasses.)

Started: Ian Broinowski, with cultural advisor Jim Everett-puralia meenamatta, The Pakana Voice: Tales of a War Correspondent from Lutruwita (Tasmania) 1814-1856 (Battery Point, Hobart: Ian Broinowski, 2019) ISBN 9780244509934