Mary Douglas 3: a positive spin on grid-group

In the negative gist (substack) I riffed on the context for page 212, of the 2017 biography of Mary Douglas, which lists the misunderstandings people have of her work.

So here I will try to put down a positve version, if not a definition. It will be based on my reading of her work, which is by no means complete.

When I read in the late 1990s Douglas' Thought Styles: Critical Essays on Good Taste (London: SAGE publications, 1996) I was reading it with the context of chaos and complexity theory of the 80s and 90s, which had by then completely taken over in Systems Theory in excitement, and subsumed the word cybernetic that Norbert Wiener promoted.

(ooh someone has written on this era, see Seising, Rudolf. “Cybernetics, System(s) Theory, Information Theory and Fuzzy Sets and Systems in the 1950s and 1960s.” Information Sciences 180.23 (2010): 4459–4476. ScienceDirect. )So my first version of Mary Douglas’ grid-group theory immediately latched onto the idea of individuals choosing, and not just rejecting in a negative sense that Though Styles emphasized. I latched onto that more than the typology or sectoring of the grid-group theory that differing perception of risk map (I provided my own microfoundations see below).

The key thing was that these groups arose by people making choices iteratively, in feedback with each other (fashion and uniforms) and that those choices then allow structures to emerge as they interact with each other (AKA as conflict). I could link this in at the time because of her work with Thompson who use information theory in its more cybernetic aspects on the general notion of feedback.

It was this focus on individual agency which captured my interest, in particular a quote in Thought Styles of Levy-Bruhl that each of us having an ‘afferent bias’.

This is not quite Mary Douglas but an interpretation of her work, and I would argue, at that time, a bit of an update. That is as an update by a theorist on these general questions.

What made Douglas' work attractive to me was her accurate descriptions of the groups that arise across populations. If they group that is, sometimes they just heckle from the sidelines, as cynical as temple dogs, as schizoid as can be.

These patterns are tendencies or preferences which in the end, in the outcome we call society, the world, never each dominate, and that a healthy society produces methods that are invigourated by the disagreements, but do not allow that to develop into conflicts that destroy the world, and in particular, it is this _noyau_ as I would call it now after Robert Yardley’s use of Petters term, that we maintain by our individual iterations, which in turn allow us to maintain solutions through time, across generations when they are not required. Our biases, even as we use then to create "identity" or "meaning" in turn use us to maintain ways of living and technologies we otherwise label as culture. I.E. the conflict between biases allows us to maintain as a species various solutions to problems that are not always there as a threat, but might be. It is the appetite or bias for the noyaux in our lives, the need to have meetings, that allows us to develop solutions, maintain the solutions for a time of need, and worry about the world, culture, and who will think of the children. Our noyaux are a type of insurance marketplace of ideas and personalities, if unconsciously so most of the time.

Conflict is not a bug but a feature. If you do it well the bugginess is no problem. If you do it badly all sorts of opportunistic infections may arise. (This is the is/ought gap dance.)

That is the view I had for some decades. I never followed up on it any research sense. Collecting data and so on. But it gelled with my sense of ‘subcultures’ we had in the 80s and 90s. Even if they were perhaps nothing more than marketing categories like generational bracketing, a commercial division which has survive better than the subcultures.

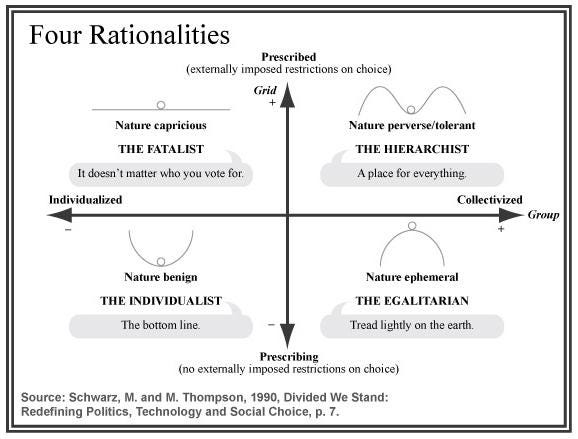

You can read about the grid-group here, and from which the following figure is taken.

In the negative gist one can see other interpretations regarded as wrong. If you are having feelings have a look at that.

Things I did not take away from the reading of Thought Styles were anthropological (or sociological) terms like institutions or rituals. People choosing was good enough for me, as was the word bias to describe the tenor or inclinations of that choice. I had already decided that bias was key to explain society, or people at least, and that to explain bias away or overcome it was to miss the main game or inquiry.

Overcoming bias is one thing in technical discussions, but to remove it from the field of study of the world or society, in assumption or suppression is to gut the phenomena, even if one does it in the name of removing the bugs of conflict in the noyaux. Then one will never see the features it brings out in us.

What I like most about the grid-group method was not the quartering of the population into instantiations of each box, but the mapping to bias as described by perceptions of risk.

In Thought Styles this was done with reference to Nature, with the risk to nature of our activities. What is your bias?

Is nature fragile in the face of human activities or behaviour? Is nature robust? Is it robust within limits? Is it chaotic?At the time I think for me it was fragile, I recognised it as a bias.

Also at that time I swapped in almost immediately Morality for nature in those questions:

Is morality fragile in the face of human activities or behaviour? Is morality robust? Is it morality robust within limits? Is morality chaotic?Now, some decades later, having concluded that morality is an outcome of the settlement and negotiation of those iterated styles of thought, or biases, I would put it like this:

Is the world fragile? Is the world robust? Is the world robust within limits? Is the world chaotic?Is is arguable that ‘the world’ is a more abstract concept than nature, and less of an instantiated outcomes as morality, but all three hint at a large context for our decisions, and are that to which we orbit our individuals freedoms as choices iterated and inherited.

In anthropology the term used for this iteration is ritual, and I have to say whenever I hear the word ritual I reach for the door handle. The need to escape is less with the term institution.

The issue I have with the word ritual is that it is a term too heavily overloaded already, I do not see much difference between ritual and rites. The key feature I take away from ritual is the routine of the matter. Choices are often automatic or habitual, and while writers always stress that the everyday routines are included in the term rituals, when we say ‘daily rituals’ it is often in jocular way, as if we are having a laugh our ourselves, as if we should be, or take it all more seriously, but our humble humours prevent us from doing so. ‘Ritual’ assumes the sacred not the mundane but we will make light of that (sacredness is another outcome).

Can we just call them choices, and iterative choices if we want to be more technical. (we can also avoid that archaeology joke.) Choice allows more choice than the word ritual.

Perri 6 and Paul Richards in this 2017 biography spend quite a few pages on ‘microfoundations’ and Douglas search for some integration within those economics that deal with choice and the micro-macro Janus dance they do there. This work happened well after I read Thought Styles.

Perhaps economics needs more complexity theory in its workings.

So as an end summary, Mary Douglas grid-group work can be very broadly called a structuralism, but not as post-structuralism might criticise it, assuming those misunderstandings are taken into account. I would labelled it very loosely as a type 2 structuralism where the parts interact and the forms and instantiations and choice of semiotics arise in that interaction, and the further result is an emergent thing I would call the world. Some may prefer to call this thing 'society'.

However, this 'thing' is not then structured (unless we world it so) by the settlements or negotiations of that process as described by the grid-group mappings. The settlement is not a market price, but the rising of the sun. Perhaps Valhalla is a good metaphor after all?

The process is created by choice, but the outcome is not a choice but a negotiation, the settlement is a deal, a thing is the result of all that meeting together, so the sun rises tomorrow. Something that death cults do not appreciate.

The ‘structure’ we end up with, the daily things of our lives, are usually referred to as institutions which are very hard to define. A marriage is an institution with or without the qualifications of law and local tradition. Parenthood is an even bigger institution, such that we rarely consider it as such, overlapping as it does in a necker cube of a babushka doll with life’s reproductive process.

I quite like the Deleuzean ratio that where we have more laws then we have less institutions, and that where we have more institutions we will perhaps need less law. But that interplay is a story for another time.

In short I find Mary Douglas describes how the world works and arises, if not why we should.

(Selfhosted linkpost page on Mary Douglas)